—by John T. Pless

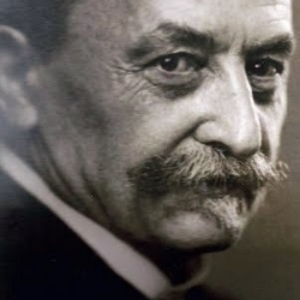

J. Michel Reu

J. Michel Reu (1869–1943), one of the most learned theologians in American Lutheran history, could hardly be classified as a fundamentalist given to knee-jerk reactivity. This irenic and deeply pastoral scholar was confident in the Gospel and devoted to the mission of making Christ known in the world. For these reasons, he responded with alarm when Lutheran church bodies in North America and Europe cared so little about the evangelical message that they let it be undermined by a failure to exercise discipline.

A case in point came in 1925 when a notorious liberal American Baptist theologian Harry Emerson Fosdick (1878–1969) was invited to preach in a Lutheran (ULCA) congregation in Dayton, Ohio. Historian Fred W. Meuser tells the story:

“In the spring of 1925, Harry Emerson Fosdick preached in a ULCA church in Dayton, Ohio, upon the invitation of the pastor; later he spoke in the chapel of Wittenberg College at near-by Springfield. Reu was especially incensed at this breach of the spirit of the Declaration [a 1920 document, “Declaration of Principles Concerning the Church in Its External Relationships”] and fully expected an official reprimand of the Dayton pastor and the college by ULCA officials. Instead, the ULCA church paper explained the Dayton incident without censure, and a Wittenberg faculty member defended the school against Reu’s charge of betraying Lutheran principles. Iowa and Ohio [Synods] were thereby strengthened in their conviction that in the ULCA individuals could do as they please in spite of official correct statements.”1

Hermann Sasse

No wonder that Reu expressed his worries about the future of American Lutheranism to his friend, Hermann Sasse. A church that cannot exercise discipline over its pastors is doomed. The failure of the leaders of the ULCA to act in 1925 was a foretaste of the future in story for most of American Lutheranism.

Doctrinal discipline would become a thing of the past, an embarrassing relic of a less tolerant time. The new tolerance forecloses on the possibility of exercising discipline over errant teachers of the church. But it does more; it robs Christ’s people of the truth of the saving Gospel. The office of the ministry is not an entitlement but carries with it accountability to the public standards of Holy Scriptures and the Lutheran Confessions. It is far more than adhering to humanly-devised bylaws and legal procedures; it requires fidelity to the teachings of Holy Scriptures and an unqualified commitment to the Book of Concord. Werner Elert’s words are to the point: “Because evangelical Lutheran confession accords with Scripture, it is intolerable for an entity not bound by this confession to have jurisdiction in the realm of doctrinal matters.”2 What Elert calls intolerable has now happened in The Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod.

Pres. Matthew Harrison preaching.

When a Dispute Resolution Panel of the Northwest District of The Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod finds that a man who time after time has repudiated the doctrine of Holy Scripture and in practice has acted contrary to his ordination vows may remain a pastor in The Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod, we have a problem. Dr. Matthew Becker’s teaching is clear and accessible in his writings. His dissent from the doctrinal position of The Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod has been thoroughly examined and carefully refuted by the Synod’s Commission on Theology and Church Relations. The catalyst for this crisis was not President Harrison, who simply followed through on the duties of his office in making it known to the church, but a district president who has consistently refused to act in accord with the church’s public confession. No amount of rhetoric can cover over the problem that confronts The Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod. Hermann Sasse wrote, “Just as a man whose kidneys no longer eliminate poisons which have accumulated in the body will die, so the church will die which can no longer eliminate heresy.”3 I, for one, am grateful that President Harrison does not want the LCMS of 2015 to become what the ULCA of the 1920’s became.

Prof. John T. Pless teaches Pastoral Theology at Concordia Theological Seminary, Fort Wayne, IN.

As an extension of LOGIA, LOGIA Online understands itself to be a free conference in the blogosphere. As such, the views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of LOGIA’s editorial board or the Luther Academy.

- F. W. Meuser, The Formation of the American Lutheran Church, (Columbus, OH: Wartburg Press, 1958), 233. ↩

- Werner Elert, “The Visitation Office in the Church’s Reorganization” in The Restoration of Creation in Christ: Essays in Honor of Dean O. Wenthe, ed. A Just and Paul Grime (St. Louis, MO: CPH, 2014), 195. ↩

- Hermann Sasse, “The Question of the Church’s Unity on the Mission Field” in The Lonely Way, Vol 2 (St. Louis, MO: CPH, 2002), 190. ↩